So, what exactly compels individuals to plunge into political activism or movements opposing a war far across the globe, in a nation they’ve never set foot in, amongst a people and culture they seemingly share no bond with?

Truly, a profound and uplifting trait of human nature is our capacity for empathy, compassion, and the expression of solidarity with those we’ve never met. Our history is rich with such instances. In the context of Iraq, as the 2003 war loomed, millions globally pushed against what they foresaw—and what indeed became—a disaster for Iraqis, whose sole fault was residing atop vast oil reserves.

Back then, I was in the U.S., leading somewhat of a dual existence. By day, I doubled for Ben Affleck on the set of “Surviving Christmas,” and by night, I was deeply involved in antiwar efforts in East LA, strategizing against the Bush administration’s march to war.

Tensions were palpable on set as reality encroached. Politics was deemed taboo by producers, fearing the charged atmosphere. Yet, silent protests emerged, with restroom walls quickly filling up with both pro and antiwar scribbles.

I remember discussing the impeding war with Affleck’s bodyguard, a former marine with time served at the Baghdad embassy. Predictably, he was all for “kicking Saddam’s ass”—a sentiment echoed by several crew members.

For six months, my every waking hour had been devoted to the antiwar cause. Joined by a diverse group—spanning ages, backgrounds, ethnicities, and beliefs—we formed a tapestry reflective of the peaceful world we envisioned. A united front of White Americans, Koreans, Mexicans, Palestinians, across all races and religions, we tirelessly worked—planning protests, meetings, cultural events, and coordinating with various organizations, unions, and religious groups. It was a deeply significant chapter of my life.

Despair, rage, fear, and sorrow hit me hard when bombs began falling on Baghdad on March 19, 2003. I was on the Affleck set, which I’d grown to detest. As filming ended, I rushed to the ANSWER Coalition’s LA office, where activists were glued to the broadcast of Baghdad under siege. We sat in silence, fixated and horrified.

It was agonizing to think that such horror could occur in the 21st century, enabled by a supposed democracy acting on dubious claims and falsehoods.

Reflecting on this, I was struck by the broader narrative of Western history—rife with deception and the pretense of benevolence, while our legacy is marred by exploitation and oppression, our monuments a testament to countless lives damaged under the guise of progress. This, I believe, is the enduring lesson of Iraq, even after two decades.

When the war commenced, a protest was quickly arranged for the following day outside LA’s Federal Building—a frequent site of my past activism.

Faced with a choice between the film set and the demonstration, my decision was clear. The movie’s importance paled in comparison to standing against the war. I phoned a production assistant early next morning, resigning to join the protest.

In the grand scheme, my absence from the set wouldn’t alter the war’s course, but my conscience demanded action.

Decades on, the war and occupation’s legacy of turmoil and destruction is undeniable. Lives were shattered; rather than liberating Iraq, the war ignited a sectarian bloodbath, ultimately spawning the horrific rise of ISIS.

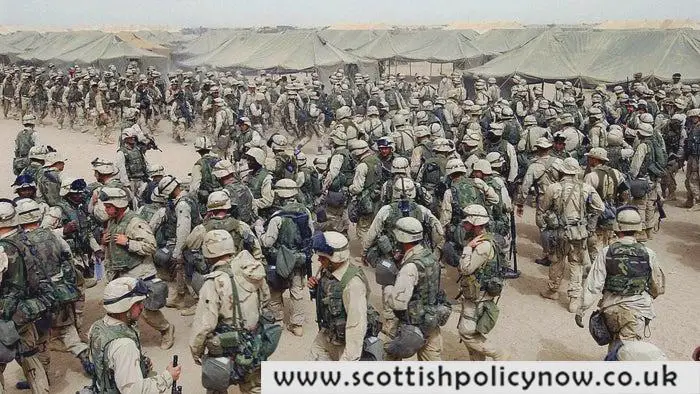

We also mourn the fallen soldiers—179 British, 4,586 American—and their families’ enduring anguish. The financial cost to taxpayers was astronomical, funding a grotesque venture to remold the region in America’s image.

In 2003, the world’s wealthiest nations waged a war over oil against one of the poorest. The architects of this atrocity remain unaccountable, challenging the very notion of Western civilization.

Gandhi’s words resonate profoundly: Does it matter to the victims of war whether the destruction is justified by totalitarianism, liberty, or democracy?